Nation's top pain doctors face scores of opioid lawsuits

By Roger Parloff , Editor-in-Chief, Opioid Watch

Update: Since this article's publication, Dr. Andrew Kolodny has disclosed that he has have served as a paid consultant to public entities that were suing opioid manufacturers.

Four of the nation’s leading pain doctors, who spearheaded a medical movement to treat chronic pain with opioid drugs, have been named as co-defendants in scores of lawsuits filed by cities and counties against opioid manufacturers.

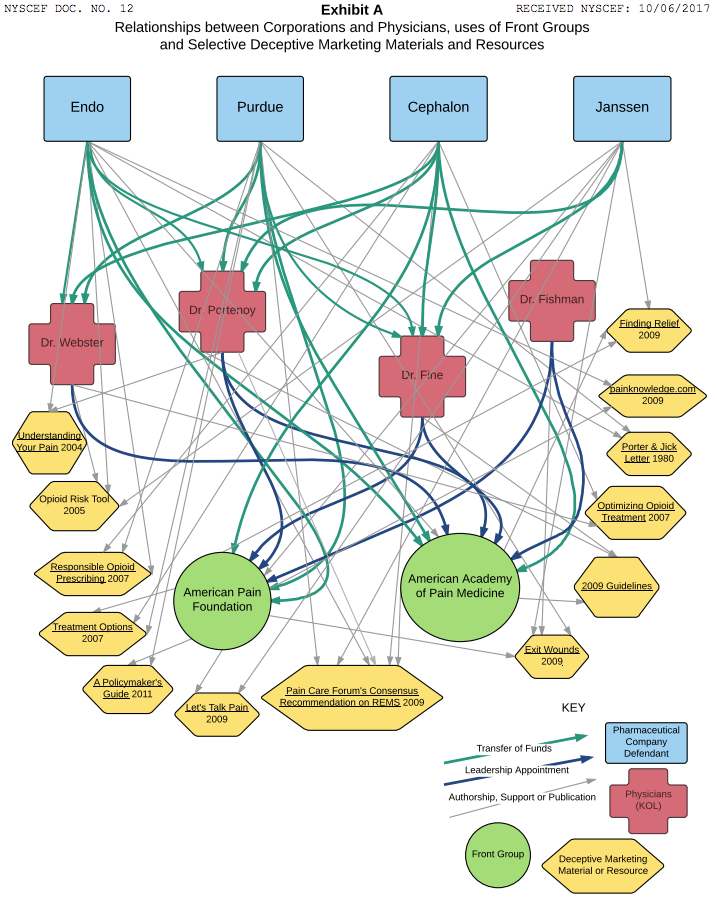

The lawsuits allege that the doctors allowed themselves to be used by manufacturers, as part of a false, industrywide marketing campaign, thereby helping to instigate the public health crisis that has led to more than 300,000 opioid-related overdose deaths since 2000.

The key manufacturers named are Purdue Pharma (maker of OxyContin); Teva Pharmaceuticals (owner of Cephalon, maker of Actiq and Fentora); Johnson & Johnson (owner of Janssen, maker of Duragesic); Endo Health Solutions (maker of Opana, Percodan, and Percocet); and Allergan (formerly Activa, formerly Watson Laboratories, which sold Kadian).

The luminary doctors are Lynn Webster, Perry Fine, Scott Fishman, and Russell Portenoy. Because they allegedly accepted tens of thousands of dollars from opioid manufacturers—for research, consulting, speeches, honoraria, and continuing medical education seminars—and led organizations that also received substantial industry funding, plaintiffs lawyers assert that their messages became tainted, and that they overstated the drugs’ efficacy and understated their risks in ways that were scientifically unsupportable.

A lawyer for Webster, Fine, and Fishman declined comment on the suits, as did Portenoy. The four doctors have asked judges to dismiss the accusations against them for failure to allege a legally recognizable claim. The co-defendant manufacturers have all denied wrongdoing.

Three pain authorities face more than 80 suits each

Three of the defendant doctors—Webster, Fine, and Fishman—are defendants in at least 80 of the more than 430 lawsuits now pending in federal court, and in a couple dozen more in state courts, according to two plaintiffs lawyers. The fourth, Russell Portenoy, a neurology professor at Albert Einstein College of Medicine and the chief medical officer at Manhattan’s MJHS Hospice and Palliative Care Center, has been named in a smaller number of cases, including at lead 18 in federal court. Portenoy has been sued less often, a plaintiffs lawyer says, because he lacks insurance.

In the lawsuits, plaintiffs lawyers refer to the four doctors as “key opinion leaders,” or KOLs, a term used by the marketing departments of pharmaceutical companies for especially influential physicians they seek to influence. The manufacturers are said to have used the KOLs for “unbranded” marketing, thereby evading the strictures of branded marketing, which is closely supervised by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration.

“Although some KOLs may have advocated for permissive opioid prescribing with honest intentions,” alleges one typical complaint, filed in the Suffolk County supreme court in Central Islip, N.Y., “[manufacturers] cultivated and promoted only those KOLs who could be relied on to help broaden the chronic opioid therapy market… The KOLs knew, or deliberately ignored, the misleading way in which they portrayed the use of opioids to treat chronic pain to patients and prescribers.” (That complaint was authored by attorneys Paul Napoli, of Napoli Shkolnik, and Paul Hanly, Jr., of Simmons Hanly Conroy.)

Webster’s clinic raided, but never prosecuted

From 1990 until 2010, Webster was the CEO and medical director of the Lifetree Pain Clinic in Salt Lake City, Utah. He is the author of The Painful Truth, a book published by Oxford University Press, and a documentary of the same name. In each, chronic pain sufferers tell their stories, and discuss the difficulty they have getting opioid prescriptions filled because of doctors’ or pharmacists’ suspicion that they are drug addicts.

He is also a past president of the American Academy of Pain Medicine (AAPM), a professional society that received, plaintiffs allege, about $2 million from opioid manufacturers from 2009 to 2013. Plaintiffs allege that he received nearly $2 million in funding from Cephalon over the years, on top of money from Purdue and Endo. Webster’s clinic was raided by the U.S. Drug Enforcement Agency in 2010, but the U.S. Attorney declined to prosecute in 2014.

In 2013 Webster was quoted by the Milwaukee Sentinel saying that as many as 20 patients at his clinic may have died of overdose, counting suicides. A year later he denied having said that, explaining that some clinic patients had died in spite of treatment, not because of it. (A spokeperson for the AAPM writes in an email: “As a professional medical society, the American Academy of Pain Medicine is committed to integrity and transparency in all of its activities. The Academy’s policies prohibit its education and advocacy positions being compromised by outside influences, such as pharmaceutical companies, just as newspapers and other media outlets don’t allow advertising to compromise their editorial integrity.”)

Perry Fine, a professor at the University of Utah, and Scott Fishman, chief of pain medicine at UC-Davis Medical Center in Sacramento, are also past-presidents of AAPM, and each has written influential articles, books, or treatment guidelines in the field. Fishman chaired the American Pain Foundation, a patient advocacy group that, by the time it was dissolved in 2012, was nearly 90% funded by industry, including 50% by opioid manufacturers.

Portenoy, who rose to become founding chairman of the department of pain medicine at Mt. Sinai Beth Israel Medical Center, authored a seminal 1986 study that triggered a revolution in opioids prescribing practices. Until then, the drugs were used almost exclusively for managing acute (i.e., short-term) pain in hospitals or assuaging the misery of terminal cancer patients. His study concluded that long-held fears of opioid dependency were overwrought, and that such drugs could be used to treat chronic pain, too, running little risk of addiction—at least in patients with no history of substance abuse. Though his study involved just 38 patients and contained multiple caveats, it kicked off a major rethinking of conventional wisdom. Portenoy and others argued that the medical profession had been needlessly forcing patients to endure excruciating pain due to unfounded fears of drugs that had been unfairly stigmatized.

$8 billion in opioid revenue in 2012; $3.1 billion from OxyContin

The idealistic doctors who led this movement were eventually handed megaphones by opioid manufacturers, like Purdue (which launched OxyContin in 1996). The companies helped raised the physicians’ profiles by funding their research, speeches, and CME talks. At continuing medical education sessions of the period, it was often taught that the chance of a chronic pain patient developing opioid-dependence was less than 1%. Few would endorse that claim today—though some still do.

In the late 1990s Purdue boosted OxyContin with the largest and most sophisticated marketing campaign ever seen for a narcotic, reaping blockbuster profits. Other manufacturers offered competing products. In 2012, companies were making $8 billion from the sale of opioids, according to the plaintiffs, of which $3.1 billion went to Purdue from OxyContin sales.

But by the early 2000s, as overdose deaths began to pile up—linked largely, at that time, to the abuse of OxyContin—skeptics noticed that the literature being relied upon for claims of low addiction risk was shockingly thin. An oft-cited 1980 report in the New England Journal of Medicine, for instance, turned out not to be a study at all, but rather a five-sentence letter to the editor, referring to two physicians’ experience with hospital patients treated for acute pain (not chronic), and who had never been, in any case, followed up with after leaving the hospital.

“It was pseudoscience”

In 2003—nearly 15 years ago—New York Times reporter Barry Meier confronted Portenoy with the weaknesses in three then-commonly cited studies. “It was pseudoscience,” Portenoy acknowledged then, according to Meier’s 2003 book about OxyContin, Pain Killer: A ‘Wonder’ Drug’s Trail of Addiction and Death. “I guess I’ll have to live with that one.”

Portenoy was back in news in late 2012, when he told the Wall Street Journal, “We didn’t know then what we know now.” The paper quoted him telling an unidentified doctor during a 2010 video interview, “I gave innumerable lectures in the late 1980s and ‘90s about addiction that weren’t true.” Still, Portenoy told the paper, he was wary of the “pendulum” swinging back too far toward irrational stigmatization of opioids, to the detriment of patients in severe need whom opioids could benefit.

The unidentified doctor in the Journal story was Andrew Kolodny, co-director of the Opioid Policy Research Collaborative at Brandeis University, who has since posted other excerpts from the 2010 Portenoy video on the web site of Physicians for Responsible Opioid Prescribing (PROP), of which Kolodny is executive director. In one of those Portenoy recounts citing “avenues of evidence” in his lectures to primary care doctors that were not “real evidence.” Still, despite these admissions, Portenoy’s past misstatements may not amount to intentional falsehoods, which is what they’d have to be for him to be liable on the legal claims he’s charged with. “Because the primary goal was to destigmatize,” he says, “we often left evidence behind.”

“It was a lot of money”

Jane Ballantyne, a professor of anesthesiology and pain medicine at the University of Washington, says that, with the exception of Webster, she knows the defendant doctors well. (She is now co-editing the fifth edition of a pain textbook with Fishman.)

Ballantyne became concerned about the use of opioids for chronic pain after research by her unit, published in 2003, suggested that opioids “can make pain worse, not better,” and that patients were “struggling with dependence,” as she recounts in an interview. Today she is president of PROP, a group seeking to cut back on the use of opioids to treat chronic pain.

Asked about the lawsuits’ accusations, she responds: “They’re friends of mine. I believe they acted out of passion to advance not only the pain care of people who might have been ruined by pain but also their own careers. And that’s normal. That’s what we all do.”

In the United States, she continues, for a clinician to gain stature through research and publishing, “you do need to take drug company money because no one else is going to pay for it.”

“So what you can accuse them of,” she continues, “is: They probably did take more money than the average person does, number one. They didn’t question why it was so easy to. It was a lot of money. The other is: They didn’t question the scientific veracity of what they were promoting. What is more difficult is: What was their intention?”

This article is contributed by Opioid Watch, an independent, nonprofit news service of The Opioid Research Institute. The Institute is funded by the Joseph H. Kanter foundations. The Institute does not accept funding from the pharmaceutical industry.

Roger Parloff is Editor-in-Chief of Opioid Watch, a nonprofit news service of The Opioid Research Institute. Parloff is a former editor-at-large at Fortune Magazine, and has been published in Yahoo Finance, Yahoo News, The New York Times, ProPublica, New York Magazine, and NewYorker.com, among others.

This post was updated on May 29, 2018.

Yahoo Finance

Yahoo Finance