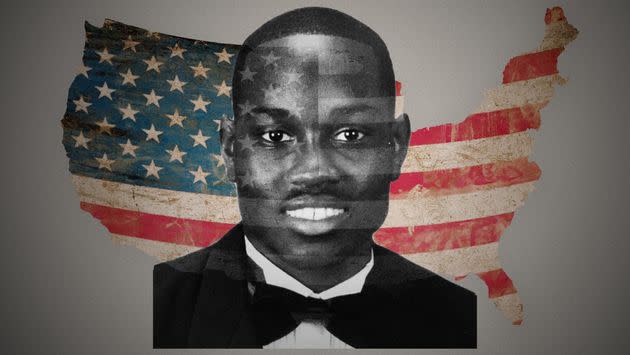

They Were Convicted Of Murder. Now The Men Who Killed Ahmaud Arbery Face Hate Crime Charges.

In November, Ahmaud Arbery’s family saw a glimpse of justice. Three men — Travis and Gregory McMichael, a father and son, and William Bryan — were all convicted for murdering the 25-year-old man in February 2020.

But their quest is not over. The McMichaels and Bryan will face a hate crime trial in federal court on Feb. 7, when jury selection begins. The Department of Justice filed the charges last February, saying the McMichaels, who are white, targeted Arbery, a Black man, “because of his race and color.”

They face possible life sentences. The McMichaels already received life sentences without the possibility of parole for the murder, while Bryan was sentenced to life with the possibility of parole.

“This case is a litmus test as to where our judicial system is,” Lee Merritt, the attorney for Arbery’s family, told HuffPost. “We will have a chance to see the grisly facts and images the nation has become intimately familiar with, reconciled with the hate and ideology that motivated those actions.”

The trial will be a stark difference from the state trial, where prosecutors hinted at a racial motive but never presented evidence to that effect — even though some was available, including the alleged use of racial slurs during the murder. While Glynn County prosecutors stuck strictly to the mechanical facts of whether the three men unjustly took a life, federal prosecutors will seek a more profound judgment: one that says crimes motivated by prejudice should be considered a crime against the whole country.

Arbery’s death — and the subsequent long delay before charges were filed — did spark a wide conversation about how cheap Black life can be in America. “There is something so simple and tragic about a young man not even being able to run and jog in public in America,” Brian Levin, a hate crime expert and attorney, said. “It is not only the tragedy and the loss of Arbery, it was mounting to the beginnings of a lynch mob.”

A Different Legal Standard

In Glynn County, the prosecution focused heavily on the legal standard of murder and Travis McMichael’s claim that he was simply executing a citizen’s arrest.

Lead prosecutor Linda Dunikoski, at times, made arguments that contained a slight — but never explicit — nod to racial animus on the part of the McMichaels and Bryan.

“We are here because of assumptions and driveway decisions. All three of these defendants did everything they did based on assumptions. Not on facts, not on evidence. On assumptions,” she said during opening statements.

But the prosecution never introduced evidence, for example, that Bryan told law enforcement officials that Travis McMichael shouted out a racial slur toward Arbery after gunning him down, uttering, “f***ing n****r” after the shooting over Arbery’s body. Defense lawyers asked prosecutors not to ask about it in court because Bryan was the only witness of the alleged incident.

The judge presiding over the case heard arguments from lawyers on Friday about racist text messages and whether they should be admitted as evidence. The content of the messages is not clear, but Bryan’s lawyer concedes they are “highly inflammatory.” He argued that disclosing the texts in court would unfairly sway Black jurors.

In May 2020, Georgia Attorney General Chris Carr requested a federal probe from the U.S. Department of Justice into Arbery’s death.

In the federal indictment, the McMichaels and Bryan are all charged with attempting to “forcibly hold and detain Arbery against his will,” which resulted in the young Black man’s death. The three, also charged with kidnapping, are alleged to have restricted Arbery of his “free movement” and “corral and detain him against his will, and prevent his escape.”

The hate crime charges focus on the motivations of the three men when they were chasing Arbery in broad daylight.

The day Arbery was murdered was not the first time he was being chased, Merritt said. It was a reoccurring “hunt” that resulted in the death of a young Black man. This was evident in the murder trial, as the McMichaels made 911 calls about a Black male walking in and out of a construction site months before Arbery was murdered.

The legal system in Georgia will also face scrutiny. Merritt said the jury on the federal trial will hear “revealing things” about what Waycross Circuit District Attorney George Barnhill “felt about Black people.” Barnhill recused himself from Arbery’s case, but not before he wrote a letter to Glynn County police arguing that the three men shouldn’t be arrested. He argued that the McMichaels were lawfully following a burglary suspect “with solid first hand probable cause.”

Barnhill was the second prosecutor to touch the case of Arbery’s murder after former Brunswick District Attorney Jackie Johnson recused herself from the case because she knew Gregory McMichael.

“We already had the criminality of their actions adjudicated before the court of law. The federal charges are going after the terroristic aspect of their actions and the implications they had for Black people of this country,” Merritt said.

“What is on trial now is not their behavior, but their reasoning for the behavior. This is an issue that has not been taken up yet, it is an issue of first impression.”

Shifting Laws Around Hate Crimes

Before Arbery’s murder, Georgia was one of four states without hate crime laws on the books. But that eventually changed.

Georgia enacted a hate crime statute in June 2020, months after Arbery’s death, and later repealed its citizen’s arrest statute. The legislation imposes penalties for crimes that are motivated by a person’s race, religion, color, religion, national origin, sex, sexual orientation, gender or disability — but the McMichaels and Bryan could not be charged under it, since the law was not in place at the time of Arbery’s murder.

Forty-seven states now have hate crime statutes on the books. But bias motivations in hate crime statutes vary statewide. South Carolina, Wyoming and Arkansas are the only remaining states without hate crime laws.

There are five federal hate crime statutes that federal prosecutors use when determining if a person should be charged with a hate crime.

There is a bigger picture here, which is the history of this country with Black people being killed for racist motives.Heidi Beirich, chief strategy officer of the Global Project Against Hate and Extremism

The Matthew Shepard and James Byrd Jr. Hate Crimes Prevention Act of 2009, which was introduced under the administration of former President Barack Obama, makes it a crime for someone to be injured or assaulted with a dangerous weapon due to their race, color, religion, national origin, gender, sexual orientation, and other protected categories.

The case of James Byrd Jr. dates back to 1998. Like Arbery, Byrd had been murdered by three white men.

Byrd accepted a ride from Shawn Berry, Lawrence Brewer and John King, all of whom were white supremacists, in Jasper, Texas. Instead of taking Byrd home during the ride, they severely beat him and chained him by his ankles, dragging him with a pickup truck.

After Byrd’s lynching, Texas enacted its own hate crime law.

Experts view the murder of Byrd and the enactment of the act as a pivotal moment in American history and also something that was long overdue.

“I think it is noteworthy under the Shepard Byrd act, which were two other cases that captured the soul of good America at a time when we are looking at increases of racial violence,” Levin said.

Arbery’s family rejected a plea deal in the federal hate crime charges on Jan. 7, even after the men were convicted of murder in Glynn County.

His mother, Wanda Cooper-Jones, told the media that the three men need to stand trial again for their brutal actions.

A Climate Of Hate

Hate crimes against Black people jumped nearly 40% from 2019 to 2020. And 2020, the year Arbery was murdered, saw the most hate crimes in the country since 2001, according to the Leadership Conference on Civil and Human Rights.

The year Arbery was killed, protests across the country followed the murder of George Floyd by a police officer as well as the fatal police shooting of Breonna Taylor in Louisville.

During this time, 61% of hate crimes showed people were targeted because of their race, ethnicity or ancestry, according to statisticsreleased by the Federal Bureau of Investigations. White people comprised 55% of the perpetrators who committed hateful acts.

From 2010 to 2019, hate crime numbers recorded by law enforcement increased by 10%. From 2015 to 2019, nearly half of hate crimes were motivated by anti-Black or anti-African American bias.

The Department of Justice says Attorney General Merrick Garland has made confronting hate crimes a “top priority” and said it is rooted in the department’s “foundational history” of combating racial violence and protecting civil rights, according to department spokesperson Areyele Bradford.

“Hate crimes impact not only specifically targeted victims, but they also instill fear across communities at large — regardless of whether they gain broader attention nationally,” Bradford said. “Consequently, the prosecution of hate crimes vindicates the rights of not only specifically targeted victims, but of larger communities as well.”

Hate crime experts who have studied America’s racist and alt-right-adjacent groups over decades believe the trial will be critical.

“There is a bigger picture here, which is the history of this country with Black people being killed for racist motives. That is why the hate crime charge is so important because it is also a societal reckoning. A Black man targeted because he is a Black man,” Heidi Beirich, the chief strategy officer of the Global Project Against Hate and Extremism, told HuffPost. “Just convicting these folks for murder is not enough for the nature of this crime.”

This article originally appeared on HuffPost and has been updated.

Yahoo Finance

Yahoo Finance